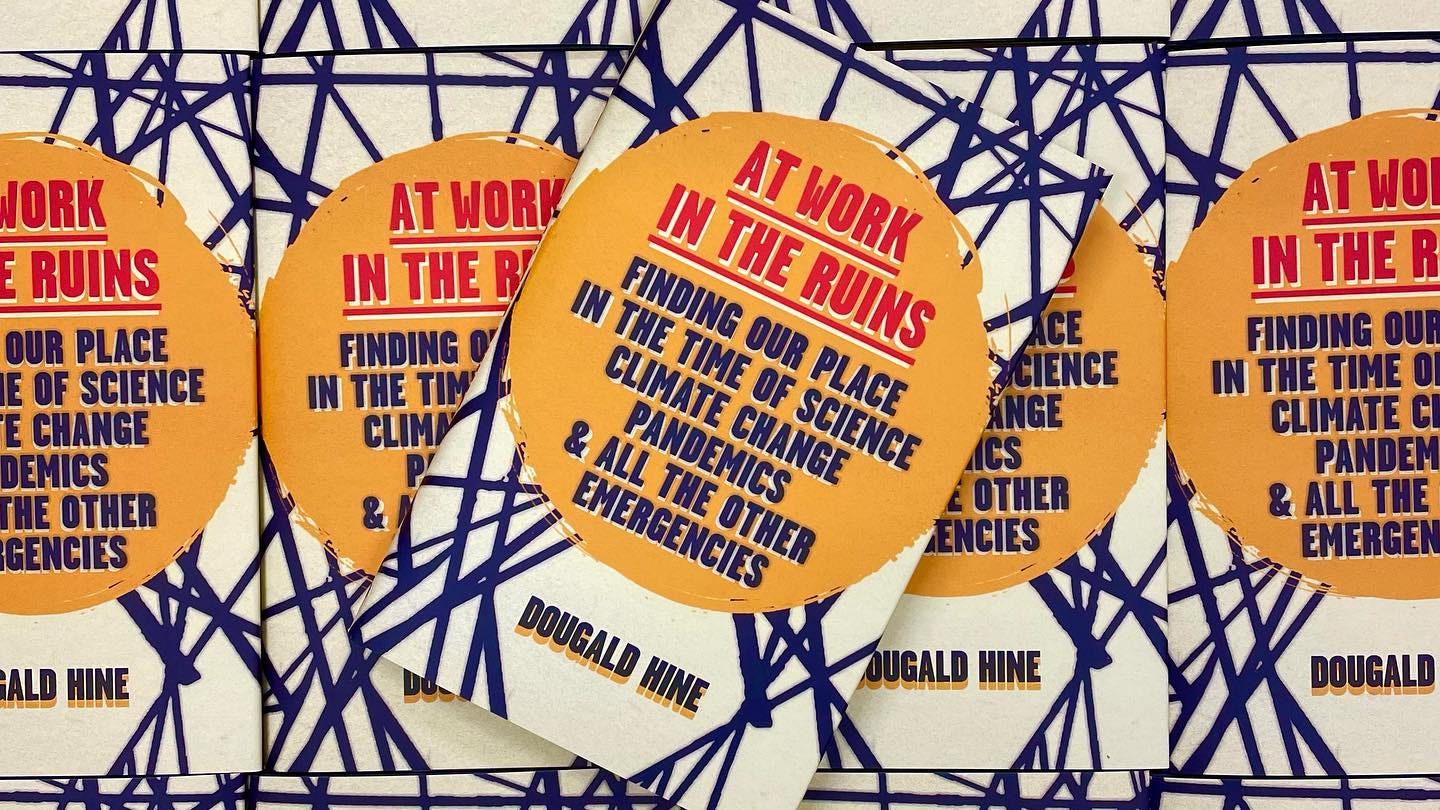

I took this photo from the window of the train this morning. Not a bad view to start the day with, on this publication day! Because yes, as of now, At Work in the Ruins should be available wherever you get your books. You can also listen to me read it as an audiobook.

Yesterday, I spent the afternoon in an empty shop in central London with thirty people – climate activists, church leaders, civil servants, the former editor of the British Medical Journal, my aunt who spends her retirement coordinating food banks and warm spaces in the north-east of England – gathered around the questions framed in the book. Afterwards, I slipped away to catch the sleeper train for the north of Scotland. I’m going to take a couple of quiet days away from emails and news alerts, to let the book speak for itself, while I catch my breath and have some quieter conversations. Then on Saturday night, the public events begin – some of these are close to selling out, so do book now if you plan on joining us.

Thanks to everyone who has supported me along the journey, not least all of you who have been spreading the word and sharing in my excitement.

On Tuesday, I shared with you an alternative opening that didn’t make it into the final text – so today, I thought I would share a passage from the book itself, the closing section of the chapter that introduces the whole thing.

‘In these times, all we can do is be a sign,’ a father tells his daughter in Ben Okri’s novel The Freedom Artist. ‘We have to help to bring about the end of the world.’ We must do this, he goes on, so that a new beginning can come. ‘But first there must be an end.’

It matters which world we think is ending, and it matters what we tell each other is worth doing in such a time. Among the people we’ll meet in the story I tell in the pages ahead are those who have dedicated their lives to the study of climate science, those taking desperate measures as activists to break the trance they see around them and those inside existing institutions who have been shaken to the core by what we know and what we have good grounds to fear about the trouble in which we find ourselves. There can be a danger in allowing that trouble to be defined solely in terms of climate change, but I’m convinced of the importance of each of these roles in these times. I’m also convinced that other roles need playing and other kinds of action are called for. There’s a lot to be unfolded along the way, but let’s have some leads to get us started, taken from a few of those who have helped to shape my thinking.

First there must be an end – but many kinds of end are possible. My friend Vanessa Machado de Oliveira wrote a book called Hospicing Modernity. The title invites us to a kind of work in which the focus is not on saving modernity, or bringing it down, or rushing to build what comes afterwards, but doing what we can to give it a good ending. To let it hand on its gifts and teach the lessons that may only become apparent as the end approaches.

‘It may seem like this book is trying to kill or destroy modernity by announcing its death,’ she writes, but this is ‘something no book can do.’ It’s a warning that applies here, too.

No one I’ve met has more to offer by way of tools for the work of hospicing, but the way Vanessa tells it, this must be accompanied by a work of midwifery: assisting with the birth of something new, unfamiliar and possibly (but not necessarily) wiser, and avoiding suffocating this new world with our projections.

The philosopher Federico Campagna speaks about living at the end of a world. In such a time, he suggests, the work is no longer to concern ourselves with making sense according to the logic of the world that is ending, but to leave good ruins, clues and starting points for those who come after, that they may use in building a world that is – as Vanessa would say – ‘presently unimaginable’.

They may be here already, the builders of that world. Some of them may have been here all along, inhabiting the ruins made by the world of the powerful. The anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing wrote a book called The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. That could be a role to take in times like these, to go looking for possibilities of life among the ruins around and ahead of us.

I don’t write to announce the end of the world or to change the minds of those who are convinced that the world as we have known it can be saved or made sustainable. I write for anyone who has found themselves, as I have, needing to make sense of what is ending, how we can talk about it and what tasks are worth taking on in whatever time it turns out that we have. Something is coming over the horizon: a humbling from which none of us will be spared, that will not be managed or controlled, but will leave us changed. Before it is over, I suspect, we will need to learn again what it means to take seriously things that are larger or smaller than were allowed to be real or significant, according to the scales and systems of modernity. We will need to dance again with the rhythms of cosmology, to be carried by the kind of stories and images in whose company – as the mythographer Martin Shaw would say – a universe becomes a cosmos. We will need to remember that we are not alone and never were, that we are part of a world of many worlds, only some of which are human. And we will need to rediscover that any world worth living for centres not on the vast systems we built to secure the future, but on those encounters that are proportioned to the kind of creatures we are, the places where we meet, the acts of friendship and the acts of hospitality in which we offer shelter and kindness to the stranger at the door. In this way, even now, there may be time to find our place within the vastly larger and older story of which we always were a part.

I am reading your book and although I am not an academic or big reader by any stretch of the imagination, I am finding your writing style so approachable and refreshing. I am just so glad of it for so many reasons.

It is a beautifully written book, the letters, words and sentences all roll together to make comfortable, relatable sense and at times poetry. So far (I have just finished part IV), you have had me sighing, laughing and crying too.

It’s an honest, balanced book and I feel that everything I’m being invited to think about is without agenda or spin.

It’s a well put together and presented book. The length of the chapters, perfectly bite size and absorbable mean that I can do a daily processing, moving clearly from one idea to the next.

It’s a deepening book. Part IV has helped me so much and comforted me whilst assisting me in working out ‘What Just Happened’!

“Life is not a statistical experience; it is inherently anecdotal. This is not an illusion or an error in our perception. The patterns that can be traced when lives are reduced to statistics do not reveal an underlying truth, deeper and more trustworthy than the evidence of our own experience. These patterns are the footprints left on a beach across which we have walked. Read with care, they have things to tell us; but they are silent about almost everything that mattered about the day we spent together on that beach.”

You cannot know how important that passage is to me and how many times I will revisit it to enjoy the feel and the truth of the words. Thank you.

I have yet to finish it, but I sent a copy to a friend and we have been reading it together, her book full of stickers, mine full of pencil scribbles, and it has certainly opened the conversation up for us two.

My thought processes have always been clunky and inexpressible at the best of times, but the last few years have added an underlying stomach churning during the day and a claustrophobic, unsettled brain at night. You have given me a vessel into which I can rest these awful feelings and the hope that we might yet “dance again with the rhythms of the cosmology”

Honestly...... thank you so much for doing this beautiful thinking on behalf of all of us.

Dougald—I found your book via a Resilience.org cross-post of an article from Andrew Curry’s blog. I finished reading your book a few days ago, and it is a magnificent piece of work. I am a voracious reader, probably around 100 books a year plus a lot of online stuff; even in that crowded field, this book was a clear standout for me.

Similar to at least one other commenter, I am not persuaded that human activity is a significant contributor to climate change. I am persuaded, however, that we are nearing the end of Industrial Civilization as we know it, due to resource depletion, pollution, and the end of cheap energy, and that significant changes are in store for human society, whether we like it or not. In that respect, we perhaps are not so far apart in our thinking after all. The beauty of your book is that people like me can disagree with some of your views and still find ourselves in agreement with your core message, that the “big path” is not the right one. My own opinion is that the path we are currently being rudely shoved down leads to dystopia.

Even if we manage a course correction in time, the adjustment will be difficult for those of us that will have to (try to?) live through the changes. But I believe the human race can survive it if done right. And I don’t think human post-industrial life needs to be bad. Especially for those born to it in the time after things have settled down to their new equilibrium, it has the perhaps surprising potential to be an even better and more meaningful time to be alive.

I just discovered your Substack after reading the book, and I'm looking forward to your future writing. I'm also following up by reading a couple of the other books you have pointed to.