As the Eurostar is about to enter the tunnel, I get a message from Liz, one further twist of the magic that has been threaded through this journey:

My friend told me the most brilliant story. She sent a copy of your book to her sister as a birthday present last week. And her sister was confused, she didn’t know if she’d bought it herself without remembering. Because a couple of weeks ago, she’d been on a train in Scotland and overheard someone re-recording an Instagram post about his book launch – each time there kept being noisy interruptions, and so she heard these little snippets about this book, over and over… And then, hey presto, it arrived in the post!

Was it only two weeks earlier that

and I were sitting on the two-carriage train that runs from Fort William to Mallaig, trying to record that clip to mark the day the book came out? Time goes strange when you travel this way.

A week ago, I woke in the Welsh borders at the home of Philip and Monica, the glass artists with whom I published a book in 2020. Philip drove me down to Ludlow to begin a zigzag Sunday journey to East Anglia.

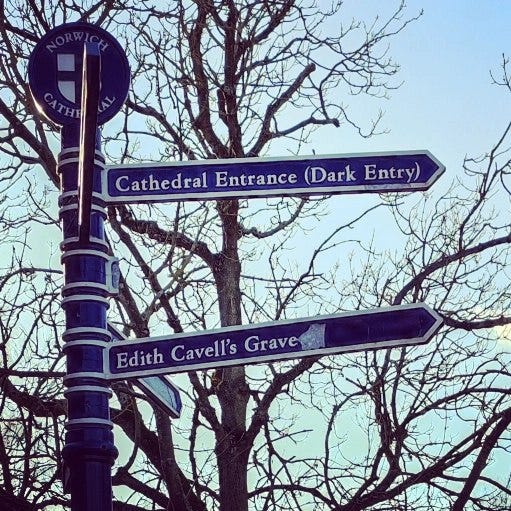

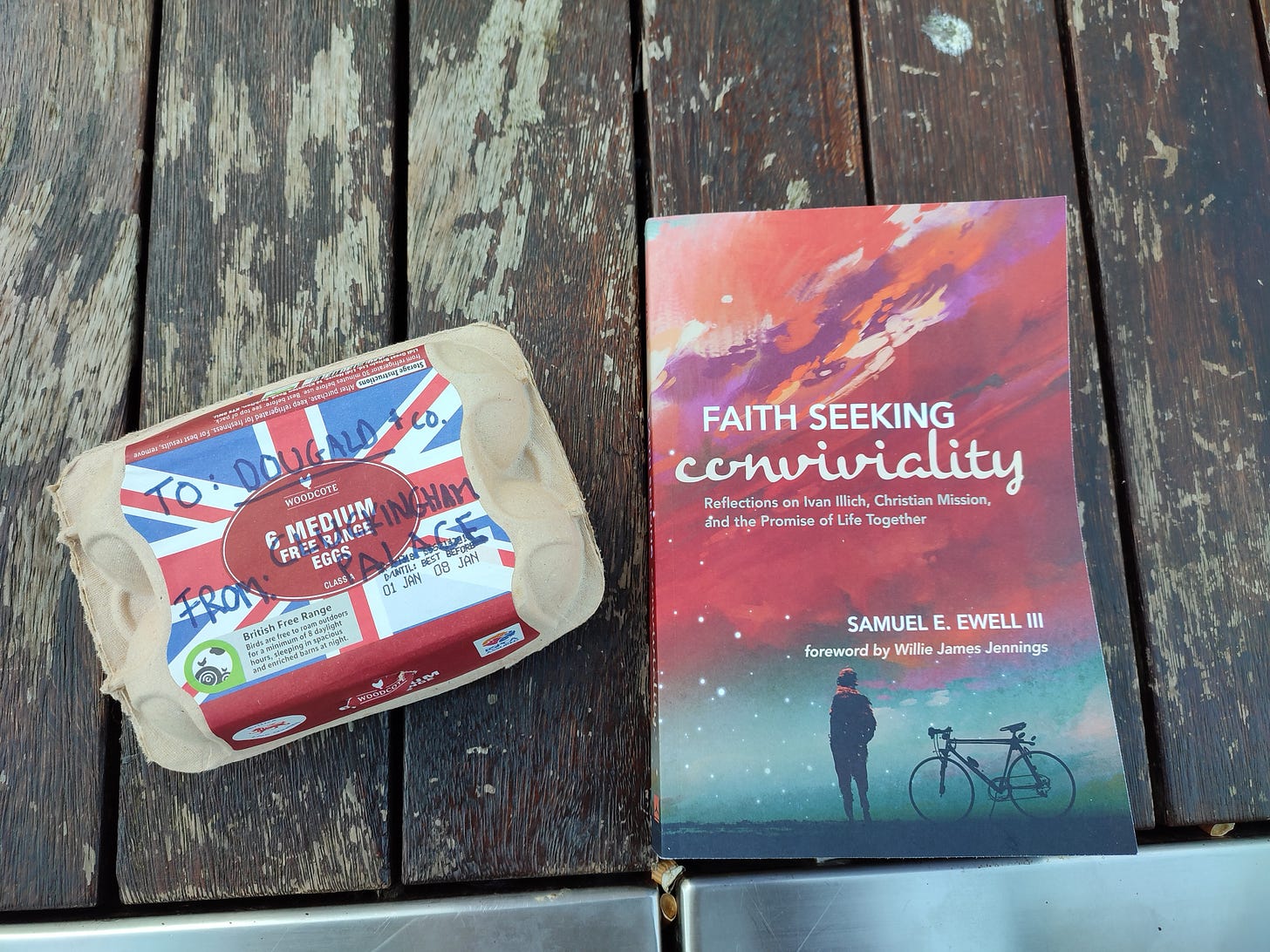

At Birmingham New Street, I was welcomed by Sam. We’d met once before, a decade ago, when he was studying for a PhD. He presented me with a copy of the book that grew out of that research and a box of eggs from their backyard chickens.

The eggs survived the rail replacement bus and two mornings later I cooked them for

and me to eat for breakfast in the kitchen of the Mill of Impermanence, where we had stayed the night with my podcasting co-conspirator Ed Gillespie.

“I feel like I’m held in a weave of friendship and mutual inspiration,” I write to Lydia Catterall.

“Not just a feeling, I reckon,” she writes back. “It’s just a truth.”

That’s how it’s been, over these weeks. I’ve been passed from place to place and from friend to friend.

On the second day of the journey, I wrote to

from the train between Hamburg and Frankfurt, “So far everything is going very smoothly and I am calmly excited, if that is a thing?”She wrote back to assure me that it is:

When stepping out to have convivial adventures, there is a sort of settled, steady fizz in the blood, like the mousse of a great Champagne, and it doesn’t feel taxing on the adrenals. So unlike the swash, backwash and roiling kind of churn that comes with the undeniable excitement of heading out to do something with a shady tinge. That always leads to exhaustion, like certain substances and their inevitable comedown.

Now, don’t let me sound too puritanical. In the course of this trip, I have been happily plied with whisky by bearded men from the Isle of Skye to Brighton – when I briefly crossed the border into Wales, I found that it’s the white-haired women who do the plying there – but still there is a cleanness to the work I have been doing, and not only because I stuck to the low- or no-alcohol beer until after I’d come off stage each night.

Stopping in Bristol, on my way from Sheffield to Devon, I sit down for half an hour with my old friend Charlie Davies. If you’ve got as far as the acknowledgements in the back of the book, he’s the one I thank “for interrupting my every sentence until I could talk in a way that had a chance of carrying, and for all the years of infuriating clarity.”

Over a sandwich, he tells me that he’s found a new piece of language for the work he does, helping people get clear about what they should be doing. “So many people have spent their lives getting things done,” he says, “but they haven’t asked themselves whether they are doing what is needed.”

The sense of cleanness, the calm excitement, the settled, steady fizz in the blood – these belong to the experience of doing what is needed, I would say.

I did ten public events and most of them were sold out. Each night had a different vibe, depending on the format and my partners in conversation and the parts of the book that we headed into. There wasn’t a bad gig on the tour, yet I still had favourites. My favourites were the nights when we went into the heart-space and the soul-space of the book.

wrote about the Brighton gig we did together, “In that kind of company, I’m running to keep up, which is deeply exhilarating.” That night was one of my favourites of the tour, because it felt like we took the whole audience with us into a place of trust. It was everything I want to do on these occasions.Once or twice, on other nights, when the conversation leaned heavily into ideas – talking about modernity or science or political history – I noticed the difference in the questions this called up. On those occasions, there were questions from the audience that had a healthy hang-on-a-minute quality to them. It strikes me that this is not just about the idea-heavy talk, but the energy with which I find myself talking. If I spoke with the gentleness of Rowan Williams, then I might get away with throwing out references that fly over people’s heads, but it strikes me that it’s a good thing that we react with caution to the combination of passionate language and ideas that are flying too fast.

In any case, when those hang-on-a-minute questions land, it gives me a chance to back up, to be present to the room and embody what I have been trying to talk about.

There were two people whose names were on my lips almost everywhere I spoke.

First, the philosopher Federico Campagna, whose thoughts I found myself paraphrasing like this:

Sometimes you are born into the ending of a world. This is a thing that happens, a thing that has happened in other times and places. How do you tell that you have been born into the ending of your world? Because the future doesn’t work anymore, it no longer sounds convincing to extend a line from the recent past, through the present, to offer a promising onward trajectory. The story of the world you were born into is coming to an end. So what do you do, if it is your discernment that you were born into such an ending? Well, you can stop trying to make sense according to the logic of the world into which you were born – and start trying to make good ruins, contributions to the jumbled legacy of this world’s ending that might prove helpful to those beginning to make the unknown worlds that will come afterwards.

The second name was that of Mohamed Amer Meziane, whose talk at the Black Elephant lectures I shared in an earlier post. Again, I found myself riffing on his words as follows:

The roots of the trouble in which we find ourselves have something to do with a strange thing that happened to the sacred. It is not that the secularising moves of modernity did away with Heaven, it’s that they relocated it. The project of modernity was to build a very literal kind of Heaven on Earth: to manifest absolute freedom and absolute security. Yet the Earth never asked to bear the weight of being Heaven. And now the Earth is groaning under that weight. And if there is truth in this account of the trouble we are in, then part of the work that lies ahead will involve bringing Heaven and Earth into some other kind of relation.

I’m still absorbing the power of these words, I’m sure their implications will feature in future posts – but having travelled the length of Britain speaking their names, it was a great pleasure to have the chance to meet both of these philosophers for the first time. On Thursday in London, my last move before catching the Eurostar was to have coffee with Federico. Then on Friday, in Paris, I was able to have lunch with Mohamed.

So many serendipitous encounters, so many happy turns of events along the way, so many friendships made within the boundaries of screens that had the chance to break into the flesh world, breathing the same air.

On the Eurostar on Thursday – just before that message landed from Liz about her friend’s sister – I’d shared some photos from London on Instagram and mentioned where I was. I got a reply from Rita Issa to say that she was on the same train. In Paris,

was waiting to greet me, and so the three of us hit the café across from the Gare du Nord. These are dear people with whom I have shared a great deal, but three weeks ago we had never knowingly met in person.The original plan for Paris had involved more meetings, but thankfully that unravelled, and so after lunch with Mohamed, I found myself free to wander the city. At his suggestion, I found my way to the Musée de la Vie Romantique and – even more stunning – the Musée Gustave Moreau. (More pictures here.)

At some point, it hit me that it must be twenty-five years to the month since I first came to Paris with a gang of friends from university. We came on the Eurostar that time, too, and one night we talked our way into a small jazz club that wasn’t sure it wanted English students in the audience, and another night we went to the Opera de Paris.

So having no plans for the evening, I thought I would check what was on – and discovered, to my delight, that it was the final night of a run of my favourite opera, Peter Grimes, Benjamin Britten’s extraordinary depiction of the tragedy that unfolds when the relationship between the village community and the dreamer who lives in the hut at the edge of the village is broken.

There was one seat available and it was the best seat in the house, in the middle of the front row of the balcon, with a considerably better view of the stage than we had in 1998. In my jeans and t-shirt, I felt just as underdressed as I had been back then, but what a glorious way to end these three weeks on the road!

Waking on the night train to snow outside the window, the mild airs of Devon and the tantalising almost-spring sunshine of Paris far behind me, there’s a message on my phone from Elizabeth Oldfield. I’d stayed with the community she is part of on my arrival in London – and I’d messaged her last night to tell her I was listening to her conversation with Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan.

“How are you feeling about the tour?” she asks.

Grateful, I think, and then another word comes to me: blessed.

DH

Dougald, it's been such a joy to follow you on your fine champagne adventure. I sense that that light, fizzing energy is part of the future that's coming towards us (rather the one that seems to lead out from under our feet that has brought us to the present from the past) as we learn how to greet with open arms whatever is drawn to us by the siren call of that fizz...

Main quest, side quest and hidden quest completed. Congrats! Now for the return, integration, and the beginnings of the next book, no doubt :)