Learning How To Drown

On becoming immortal without growing up

For the past three weeks, I’ve been travelling around Europe with my family, and the journey has sparked thoughts which will make their way into writing soon. Meanwhile, in a holiday mood, here’s a piece that grew out of an unexpected message I got the other day. (For readers unfamiliar with the British school system, I should mention that “sixth form” is what we call the last two years in high school.)

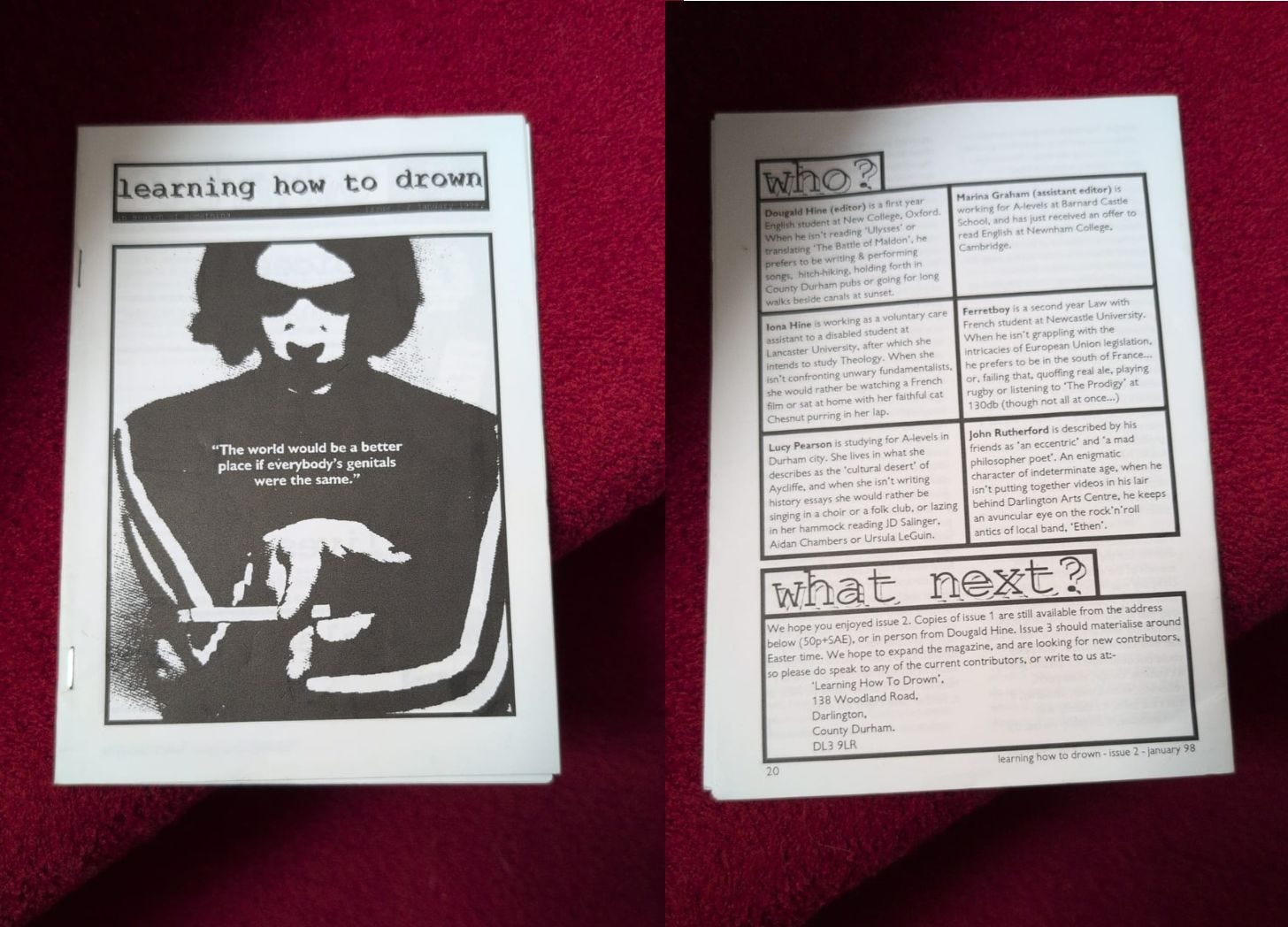

“If you’ve never read a zine before, what they are is small, self-published magazines, and they come in all kinds.” — Cindy Crabb, Doris: An Anthology 1991-2001

The sharpest, most irrefutable critical judgement I’m ever likely to receive was delivered on the steps of the Garden Bar of Darlington Arts Centre, one night in the spring of 1998, by a girl whose name I never knew.

The Arts Centre had been the scene of a good part of my growing up, not least all the Thursday nights at the folk club which met in this bar at the back, but tonight it was packed with a younger crowd for a hometown gig by Britpop hopefuls, Ethan, fronted by my longstanding co-conspirator, the multi-instrumentalist and composer Billie Bottle, in one of her earlier incarnations. It’s possible I oversold the connection between the band and the zine I was selling outside the gig. In any case, this girl took a copy, eyed it sceptically and read aloud from the cover: “Learning How To Drown. Issue 3? If it was any good, you’d only need one issue.”

“You are about to become history,” read the message on my phone last Wednesday.

This could have sounded threatening, but the sender was the younger sister of a friend from sixth form, now a teacher at the girls school in the town where we grew up. Her brother had found a copy of Issue 2 of the zine, for which he wrote under a pen name. At his encouragement, she was going to submit it to the archives of the Centre for Local Studies at the town library.

“Ferretboy fancies a shot at immortality,” she wrote. Did I want my name on the submissions paperwork too?

The question tickled me, as barely a week before, I’d been holding forth about Hannah Arendt’s assumption that we all want our names to live on in perpetuity. Maybe I just haven’t risen beyond the animal level of existence, but this idea in The Human Condition leaves me untouched. I’m not even really drawn to the Woody Allen version of immortality: “I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen, I want to live on in my apartment!” What I want is to enjoy my small part in the great play of life, to try to receive my days as a gift, even the sad and painful ones, and, sooner or later, to leave the stage, so as to make room for those who are coming after. Whether my name is remembered after my exit seems rather unimportant.

Still, given the option of this low-key entry in the historical record, I found myself saying yes.

Let me tell you how I came to start a zine.

It was July 1997 and I was on my way home at the end of ten months of busking and hitchhiking all over Europe. Probably it’s still true today that backpackers gravitate towards one another, but this was certainly how it worked when no one travelled with a phone or laptop. There were three of us among the passengers on that night’s ferry out of Bergen, and one of the crew showed us a room where we could lay out our mats and sleeping bags, rather than sleeping in the lounge. The others were in their late twenties, travelling together, travelling onwards, whereas I’d had the safety-line of a place at university to go back to. Her name was Cindy, I don’t remember his. Of all the people I met that year, they had travelled the furthest and the hardest: hitching up through the Yukon to Alaska, crossing into Siberia and trying to get to Tuva, where camels and yaks and reindeer overlap, inspired by the story of Richard Feynman’s last journey, then on across the rest of the Eurasian landmass.

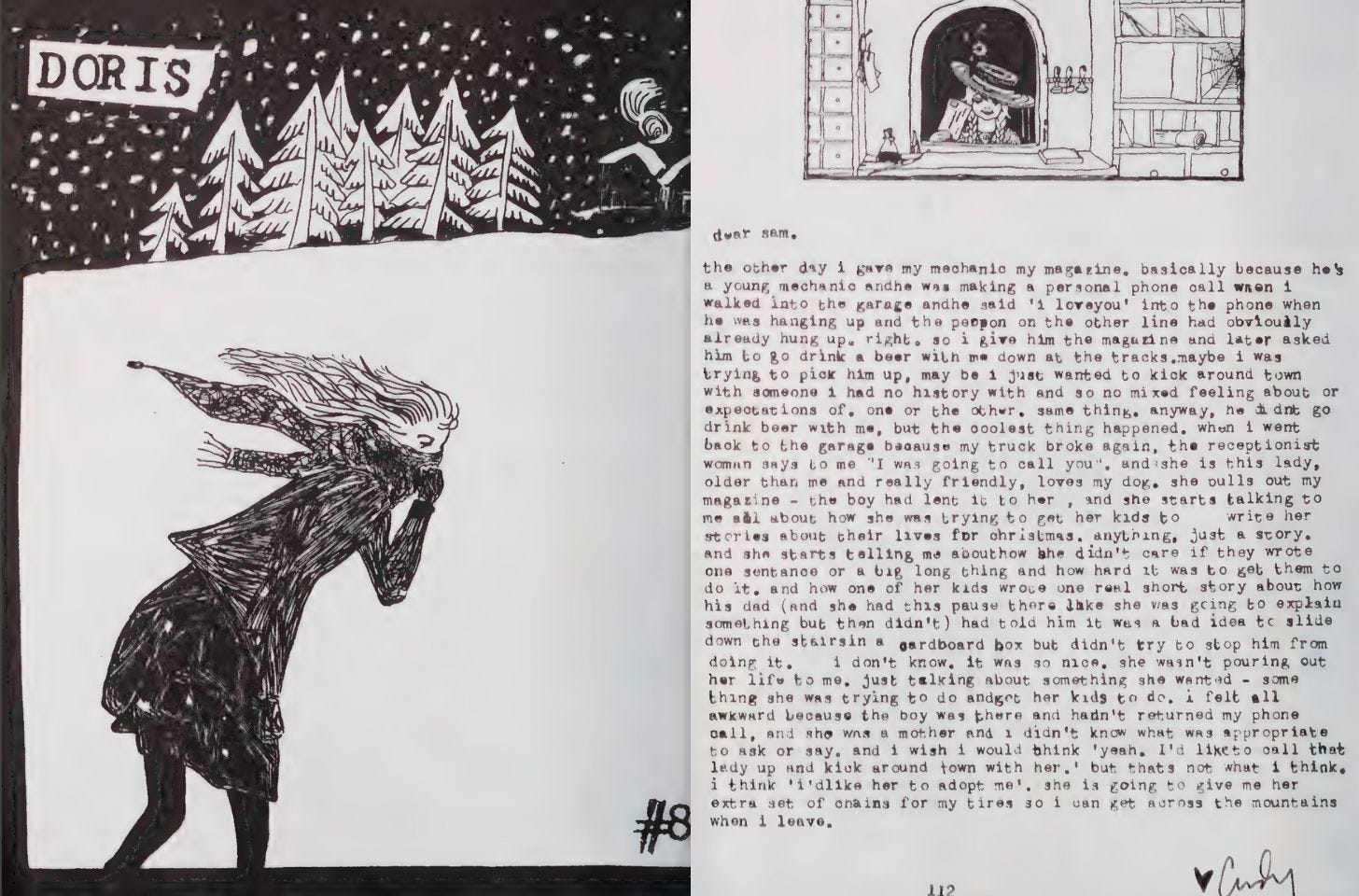

Before we parted ways the next morning at the Port of Tyne, Cindy handed me a small pamphlet, printed on soft, heavy paper. On the cover was a drawing of a woman walking in a snowstorm, face half-covered, hair and scarf blown out behind her, pine trees crowning the horizon overhead. In the top left corner was the name DORIS and in the snow at the bottom right #8. Some of the stories inside were handwritten, others typed out on typewriters or drawn as comic strips. All of them were hers. These stories were secrets shared, small human stories from her life among punks and anarchists, moments of beauty and kindness, lostness and brokenness and mending, intercut with stories that retraced younger experiences, trying to make sense of the things she had done and had done to her. Much of it was beyond my experience, places I’d never been, things I’d never even heard anyone talk about. She wrote like she was writing a letter to a friend, then she printed these letters and gave them away.

Years later, when I was part of a squatted social centre in Sheffield, I discovered that Cindy Crabb was a legend to the young punk girls running gigs in the basement, and they were amazed that I’d actually met her. At the time, all I knew was that I’d never read anything like this, never even heard of a zine before, but that this was exactly what I needed to do with the summer that was waiting for me when I got home.

Learning How To Drown. The name was a line from a song I made up one night that summer when we were jamming in someone’s flat in Middlesborough.

I didn’t have anything like the stories Cindy told, and it would be years before I learned to write that clearly. But I had the itch to write and her gift gave me permission to do what I used to do when I was seven or eight or nine years old and make my own publication with whatever came to hand. If I couldn’t imagine filling a whole zine with words of my own that summer, then I could round up a gang of friends who were up for writing for it. And one way or another, this is what I’ve been doing ever since, bringing people together to create a vessel for the things I want to write, because even now, when I actually make a living out of writing and the activities that weave around it, I’ve still never learned the knack of pitching to editors.

The aesthetic was more DTP than DIY, laid out in columns on my dad’s PC and printed on the massive photocopier at one of the local charities where he had a connection. After we’d printed the first issue, I was cornered one Sunday morning after church by Eric Hanson, a forthright Glaswegian who I realise now was the first person I knew who modelled what intellectual excitement looks like, with his rigour and generosity of mind. “It’s not unusual at your age to create a pretentious magazine,” he began. “What is rarer is to create a pretentious magazine that is actually any good.” Our zine had already made a favourable impression on an unnamed lady of the press, he went on. However, there was one important thing lacking – and he presented me with a heavy-duty office stapler, thanks to which our later issues held together rather better.

The issue I was trying to sell outside that gig in the Garden Bar turned out to be our last. There would have been an Issue 4 that summer, but then I said some stupid, pompous things to my friend Marina, who had helped me to edit the earlier issues, and she sent me an angry article which made clear how badly I’d upset her, and that was where it ended.

But the truth was it needed to end, because the zine belonged to the tail end of my teens in County Durham, while I was twenty and already a year into studying English at Oxford, and the gap between those worlds was unbridgeable. My college friend Kate wrote a piece for the third issue and I gave her a few copies. When a pair of English students in the year above flicked through them in her room, it led to a conversation which she reported back to me with discomfort; their conclusion was that northerners were just younger for their age, by a couple of years, than their fellow southerners. Actually, most of the friends back home who were writing for Learning How to Drown were still in sixth form, but to the clever and sharp-edged undergraduate world in which I was trying to find my bearings, this was an implausible choice of side-project.

One afternoon in my final year at Oxford, I remember announcing to another college friend that I had worked out what I wanted to do with my life. This got her attention and I could almost see the thought bubble: maybe Dougald is finally ready to grow up?

“I want to start a magazine that I can edit from any city in the world,” I told her, and like the payoff in a three-panel comic strip, the thought bubble was replaced: ah no, false alarm!

Now and then, in later years, I’ve thought back to that conversation, for while it was a whimsical declaration and deserving of such a response, there are days when it seems that this is more or less what I ended up doing. Like today, writing this, on trains between London and Hamburg.

If there’s appetite, then I will dig out one of the stories I wrote for Learning How To Drown and publish it as a paid subscriber post here. So if you’d like to see that, and you don’t have a subscription already, then let me know by taking one out.

The usual principle applies: if you’re feeling the pull to step closer and share in the behind-the-scenes parts of my work, but money would be an obstacle, then drop me a note and I’ll comp you a subscription for the next while.

I’m in summer mode for the rest of Alfie’s school holidays, but feeling the itch to write some shorter pieces along the way, so I suspect there will be more coming on other subjects soon. Meanwhile, thanks as always for reading and sharing and supporting.

DH

I don't know if it counts as a zine, as it's a community magazine connecting three small towns and many tiny local village hall events (and therefore deeply uncool), but several years ago I founded MidBorder News and achieved a lifelong dream, having drawn and written tiny wee magazines as a child. I've just handed it over to a new editor in order to spend more time with my sanity (such as it is) and I am both hugely relieved and bereft.

There's something delicious and wonderful about zines being the thing that survive us. Some of mine were made for one night only, to be given away when I was DJing, or to sit alongside an exhibition that lasted a day or two. And now all my zines - the ones I have made and the ones I have collected - live in the archives at the University of Kent, as the Dan Thompson Collection. Never imagined that. https://www.kent.ac.uk/library/special-collections/theatre-and-performance-collections/dan-thompson