“It was the start of an aesthetic revolution for me,” Maura O’Connor says, “from thinking fire is ugly and bad and scorched ground is evidence of a sort of tragedy, to now thinking it is absolutely beautiful.”

The image of the mega-fire and its continent-spanning drifts of smoke is one of the most potent ways in which the climate crisis is evoked. Referenced in passing at the start of an article, or dwelt on in a book-length telling, the unprecedented burning of forests triggers deep fears and is held up as evidence for why those fears are well-grounded. In the United States, a polarised politics casts a spell over the understanding of these new and frightening patterns of fire: one side only wants to talk about the role of climate change, while the other side lays all the responsibility on how forests are being managed. Meanwhile, campaigners and editors insist that people want a clear, simple story, not to be muddled by complexity.

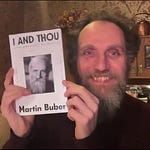

One thing I’ll say for Maura’s book, Ignition: it’s proof that attending to complexity can make for compelling storytelling. The book tells the story of her journey into the world of wildland firefighting and controlled burn fire-setting. It’s a journey that involves working alongside and learning from people whose skills are not acquired in the kinds of places where journalists are educated. It’s a world to which people arrive from very different directions, animated by a care for the landscapes with which they are getting involved, without necessarily sharing an overall analysis or framework of belief. There’s also an excitement and energy coming from the work itself, from the close involvement with this powerful and potentially dangerous element of fire.

The aesthetic revolution Maura went through began with an experience in Australia, encountering burned ground and being told that the fire had been set intentionally, for ecological benefit. There was something here that didn’t fit with anything she thought she knew about wildfire from growing up in the United States. This leads into a history of the role of fire within the landscape. By one reckoning, eighty per cent of North American ecosystems have been shaped by the deliberate use of fire over thousands of years, practices held by Indigenous inhabitants and often taken up by settlers, until new approaches to forest management criminalised these practices, treating the setting of fires as primitive and destructive. In the name of science, fire came to be treated as inherently bad, something to be avoided at all costs. The consequences of a century of this way of managing forests now collide with the effects of climate change to produce the kind of fire disasters that affect communities in many parts of North America and occupy the imaginations of millions of us elsewhere.

In reading Maura’s book and in the course of our conversation, I kept seeing patterns that connect to other stories I’ve been tracking. When she says that we need to differentiate between kinds of fire, rather than simply regard all fire as bad, I think of the story

told in his latest post of a young man declaring: “Farming needs to stop. It’s the single biggest driver of climate change.” What goes missing from discussions of this kind is any attention to context, to the differences between things that get lumped together in the same category. I’m increasingly troubled by the way that the understandable sense of urgency around the climate crisis generates an impatience with context. I think again of ’s story about watching the newly planted saplings die in the field behind his home in rural Luxembourg, because the farmer had been funded to plant trees without any provision for what they would need in order to live.I can’t see any way through the times ahead that doesn’t involve more of us being called into a closer attention to and involvement with land and food and the life of those we share it with. This pulls in the opposite direction to the “global dashboard perspective” – as

and I named it earlier in this series – which has come to dominate the response to climate change. One of the reasons I’m so enthused about Maura’s book is that it provides an unexpected example of what being drawn into this closer attention and involvement looks like in practice.By the end of our conversation, we’re talking about what it’s like to open a door in the flat surface of the world and find a path that goes deeper and deeper, a journey of learning that is endless and that you don’t want to end, because it is also a kind of falling in love. The chances are that your path will lead somewhere else than working with fire, but there’s a great example here of what it looks like to find yourself on such a journey.

As usual, the first forty minutes or so of the session was a conversation between me and the guest, and this part of the recording is free to everyone – while if you want to watch the further discussion, you’ll find it behind the paywall. (There’s also an audio recording of the whole session there for paid subscribers.)

The discussion this week was particularly powerful, as Scott and Shabe spoke from parts of Canada where fire is a present reality, while Hazel led us into the psychological depths that are hinted at in this language of fire and transformation.

Finally, I wanted to share a comment that

posted in the chat on the call:I’m just so struck by what’s made, or built, by engaging in caring breakage. It’s a very different image to the community and goodness we know can grow out of catastrophe.

We’ll be back for the last in the current season of Sunday Sessions on 16 June when I’ll be joined by Bhav Patel for a conversation about the origins and ongoing relevance of Alcoholics Anonymous to the wider predicament of modern culture. Again, the live Zoom session will be open to paid subscribers to this Substack – and if you want some reading ahead of that, then I recommend Lewis Hyde’s essay, Alcohol and Poetry.

Shownotes

Ignition: Lighting Fires in a Burning World by M. R. O’Connor is published by Bold Type.

To explore more of Maura’s work, visit her website.

Jonathan Franzen’s New Yorker article, ‘What If We Stopped Pretending?’, was published in September 2019.

My essay, ‘After We Stop Pretending’ was published by Dark Mountain in April 2019.

Stephen Pyne is the historian of fire whose work Maura refers to.

The post by

that I reference is ‘C-wrecked: agrarian transition as politics, Part 2’.During the discussion, Shabe asks about John Vaillant’s Fire Weather.

Scott mentions the Institute for Wildfire Science, Adaptation and Resiliency at Thompson Rivers University.

Here is a conversation with Elizabeth Azuz and Margo Robbins from the Yurok Tribe’s Cultural Fire Management Council.

‘Fire Bug’ is the essay Maura wrote for the New Yorker.