‘What’s more horrifying?’ Gordon White asked in a post the other day. ‘Saying nothing or talking endlessly about it?’

As I was starting to prepare for the latest episode of The Great Humbling, I found myself sitting with something Andrew said at

about having ‘been in a quiet lately’, and how he had been lifted into language again by ’s reflection on ‘how words can be written in wartime’.When Ed and I compared notes, we realised that we had both been drawn to poetry. That almost the only writing we were finding that could thread a needle between ‘saying nothing’ and ‘talking endlessly’ was coming from our poet friends, or from the pages of poets who had lived through other times of war.

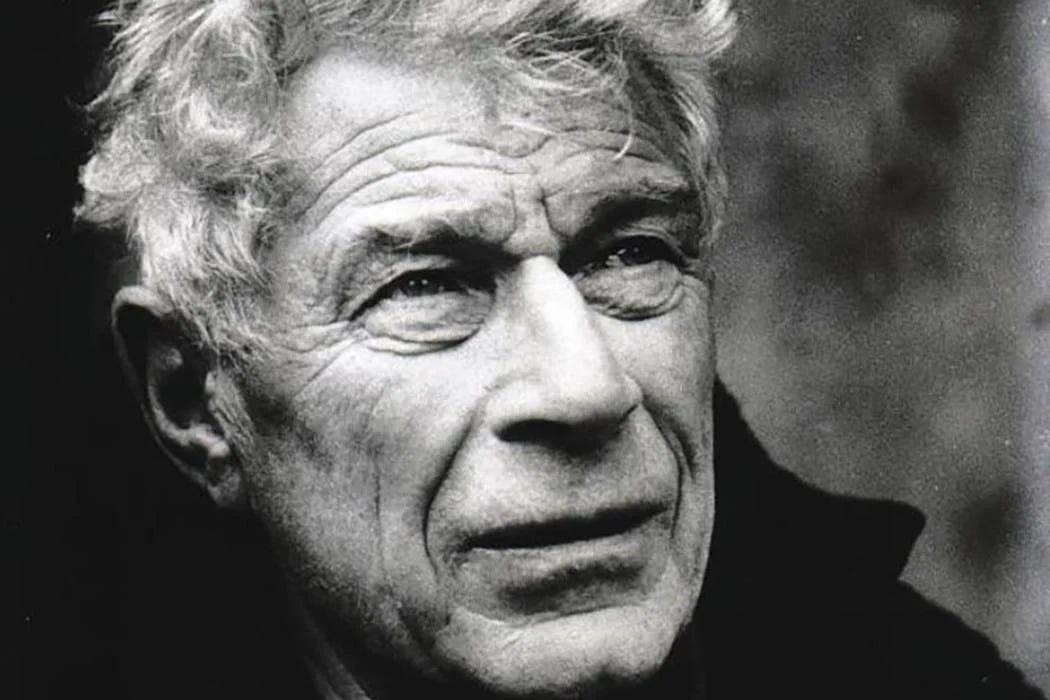

So I found myself going back to reread an essay that John Berger wrote in the early 1980s, ‘The Hour of Poetry’. And sure enough, I found what Berger has so often given me: not a smooth, complete theory or explanation, but fragments worth gathering and holding onto, along with a sense that someone has walked these paths before us.

Together with the recording of our ‘Words in Wartime’ episode, I wanted to share a little more of Berger’s essay. (You can find it in The White Bird or Selected Essays, both of which are available to borrow at the Internet Archive.)

It is not easy to read. ‘Of all experiences,’ Berger writes, ‘systematic human torture is probably the most indescribable.’ The first half of the essay is an extended reflection on torture, intercut with passages from the Chilean poet Ariel Dorfman’s collection Missing, published by Amnesty International, giving voice to the victims of torture and their families.

In the face of the monstrous machinery of modern totalitarian power, so often compared to that of the Inferno, poems will increasingly be written.

In the second half of the essay, he is concerned with why this should be the case:

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries many protests against social injustice were written in prose. They were reasoned arguments written in the belief that, given time, people would come to see reason; and that, finally, history was on the side of reason. Today this is by no means so clear. The outcome is by no means guaranteed. The suffering of the present and the past is unlikely to be redeemed by a future era of universal happiness. And evil is a constantly ineradicable reality. All this means that the resolution – the coming to terms with the sense to be given to life – cannot be deferred.

I’m reminded, once more, of Federico Campagna’s words about how it is to be born into the ending of a world. That a world, in this sense, is constituted by a story and that the marker of its ending is the inability to extend that story convincingly into the future. Under such circumstances, Campagna suggests, the first move is to stop trying to make sense, according to the logic of the world that is ending.

If poetry can go on, where prose loses the conviction it once had, then this may be because poetry is not under the same obligation to ‘make sense’.

Here is Berger, again:

The future cannot be trusted. The moment of truth is now. And more and more it will be poetry, rather than prose, that receives this truth. Prose is far more trusting than poetry: poetry speaks to the immediate wound.

(The one collection of poetry that Berger published was called Pages of the Wound. I do not have a copy, but I once borrowed it from the Poetry Library in London and I seem to remember an introduction or note in which he wrote about poetry being what he turns to when nothing else works.)

One can say anything to language. This is why it is a listener, closer to us than any silence or any god. Yet its very openness often signifies indifference. (The indifference of language is continually solicited and employed in bulletins, legal records, communiqués, files.) Poetry addresses language in such a way as to close this indifference and to incite a caring. How does poetry incite this caring? What is the labour of poetry?

Berger pauses here to stress that he does not mean ‘the work involved in writing a poem’. Rather, he is asking what poetry does. And it is this question that he is answering in the passage I quote in the episode:

Every authentic poem contributes to the labour of poetry. And the task of this unceasing labour is to bring together what life has separated or violence has torn apart. Physical pain can usually be lessened or stopped by action. All other human pain, however, is caused by one form or another of separation. And here the act of assuagement is less direct. Poetry can repair no loss, but it defies the space which separates. And it does this by its continual labour of reassembling what has been scattered.

As I write out those lines, I’m reminded of a story Berger tells in Here is Where We Meet. How his father chose to stay on for four years after the end of the Great War, working for the War Graves Commission, with its own grim labour of ‘reassembling what has been scattered’, so as to offer dignity to the bodies of the dead.

Born in 1926, Berger felt so close a connection to this part of his father’s life that he could write a poem called ‘Self-portrait: 1914–18)’. Here are some lines from that poem:

I was born by Very Light and shrapnel

On duck boards

Among limbs without bodies.I was born of the look of the dead

Swaddled in mustard gas

And fed in a dugout.I was the groundless hope of survival

With mud between finger and thumb

Born near Abbeville.I lived the first year of my life

Between the leaves of a pocket bible

Stuffed in a khaki haversack.I lived the second year of my life

With three photos of a woman

Kept in a standard issue army paybook.In the third year of my life

At 11am on November 11th 1918

I became all that was conceivable.

You can listen to The Great Humbling S5E2: Words in Wartime on our Libsyn page, on Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also find it here on YouTube:

Thanks for reading and for all your support, especially to those of you who have become paying subscribers. Your subscriptions are what allow me to dedicate time to my Substack writing and to the podcast.

DH

Thank you for this. I've been rereading Berger recently; but also thinking a great deal myself about what it means to write poetry from a position of relative privilege and certainly relative democracy, tranquillity and safety, in a no-war zone.

I know that poetry can save your life – it has mine, in certain ways, a few times – and needs to be out there; but it still can feel like an indulgence as the writer.

I've also been thinking about Adorno's dictum 'no poetry after Auschwitz'.

This is not exactly what you address, but relevantly tangential, I suppose. Relevant to being a creative: what is one's responsibility; what is one's task/duty (difficult word to use) in the face of it all?

Once again your instincts lead you to the right place.

I recently spoke at a workshop exploring the role of poetry in the climate crisis. I was conflicted, because I find when poetry is used to help a political project, it will in ways refuse and get lost. What I found myself saying is that the prose explanations are crumbling around us, while the poem remains, and poets will need to step into that new reality. Reading Berger's descripting of early protests being "written in prose" rang a giant gong for me. Poetry is often brought in to serve these prose-written movements, but that's actually kind of backwards.

Rumi has a tale describing a limping goat lagging behind the herd, which comes to a cliff and must turn around, and suddenly the goat in the back is in the front. I think there's something of that going on today.

If I were to explore Berger, what book would you recommend I begin with?