In this week’s post, I go looking through old notebooks for poems that once happened to me, and draw your attention to three books worth celebrating. Before we get going, there are still tickets available for next Thursday’s London event – and for the online series I’m teaching, which starts in two weeks’ time.

I am not a poet. Among the various nouns I’ve claimed or had hung around my neck, that’s never been one – but sometimes poems happen to me. “Poetry is where I end up, when nothing else works,” I wrote in an old notebook.

Last week, I went looking for one old poem, and stumbled unexpectedly on another. Written by a young man in 2003, it belongs to the tail-end of a long drawn-out romantic entanglement. I remember reading an interview with Nick Cave, a few years after The Boatman’s Call, in which he sneered at his slightly younger self for making such melodrama out of an ordinary heartbreak, and there was a time when I would have winced at this poem for similar reasons. But I’m kinder towards that young man now, and inclined to think that our youthful longings can be a training for a larger longing, that our ordinary heartbreaks are what carve us into the people we become.

So before I get to the poem I’d gone looking for, here is the one I found.

Hope

It is the strangest kind of haunting, jamming the works of getting on, getting over, mending and making do. The wound stays open. Something flutters, invisible, in the veins returning to the heart. Now, quieter than the night noises – the heavy sighs of trucks, the foxes’ spats – I hear it like the ticking of a clock that stands between the mind and sleep. It measures out days of unequal length: one afternoon stretches beyond time’s horizon; years of silence become a pause for breath in conversation. And I would rather lose sleep, ignore advice and go unhealed than have this ghost cast out that gives me dreams and sadnesses. While the flat figures on the digital display declare that everything is known and counted, I am listening to the echo of words that may never be spoken.

In another chapter of being young, a little later than that poem, I gathered the handful of London friends who could make it to celebrate my turning thirty in a pub on Broadway Market, stayed out drinking and dancing until 4am, slept a couple of hours, and woke to find an unexpected email from my favourite author.

Anyone who knew me in my twenties had heard me speak about Garner, Berger and Illich. In an age in which we mostly find our elders in books, if at all, these were the three I had found, three men of my grandfathers’ generation whose work I learned to steer by. Then, in a few weeks on either side of my thirtieth birthday, I saw John Berger speak for the first time, met Alan and Griselda Garner and received an invitation to visit them at Blackden, then travelled to Cuernavaca to a gathering for the fifth anniversary of Ivan Illich’s death, where I found myself welcomed into the family of his friends and co-conspirators.

Looking back on that autumn, the best comparison I can offer is to the scene in one of the Narnia books where the children are looking at a picture on a bedroom wall and then find themselves falling through its frame and into the scene. I fell from the safety of the library and into the vulnerability of human encounter, and this is a heady experience, by no means an easy one to navigate. Though one measure of how it shaped me is that it was at the end of that autumn, two weeks after returning from Mexico, that I wrote my first email to Paul Kingsnorth, setting in motion the collaboration which became Dark Mountain.

All of this came back to me last week, because it was my turn write to Alan as he marked a significant birthday, turning ninety. One of his early novels, Elidor, is a turn on the same tropes as Narnia: four children find a threshold in a bombed-out church to a dying otherworld which needs their help, and bring back four treasures to our world. But the book is far more ambivalent about such encounters and their costs, and it all lands a long way from Lewis’s “Further up and further in!”

When I started to get to know the people whose work had mattered deeply to me, these friendships were sometimes haunted by an unresolved sense of longing. Now I think of it, the feel of this had much common with those earlier, formative romantic entanglements. It took me time to learn that, in such situations, the gift has already been received. Often, all that is truly needed is to say thank you, and then to see what grows from it.

The poem that follows was written at a point where I had begun to recognise this pattern, and it’s the one that I went looking for last week.

Your Song

I have been a little boy asking for some great thing he couldn’t name but ached for. The ones he asked were those he most admired. He was not wrong, his admiration was not misplaced, and they cared, they’d give him words of encouragement, heart-spoken words. He had their blessing. It did not ease his lack. So he tried harder to find the name, to spell his yearning, to forge words that would fit the lock. It was saddening, the effort that he made, the way such effort could become a block, the opposite of learning. I have been that boy and I know now his mistake: the great thing does not want a name, it does not lie in anybody’s gift, no one else can write your song. You only have to listen. You had it all along.

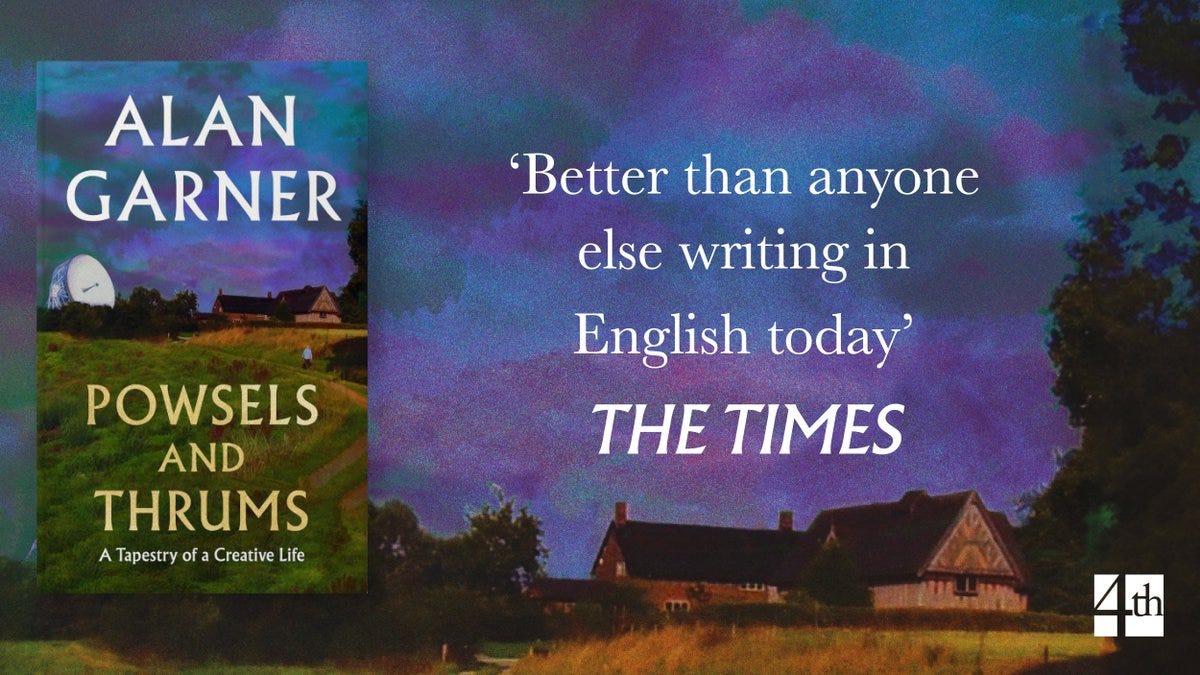

For those of you who share my love of Alan’s writing – or whose curiosity has been pricked by what I’ve written already – let me alert you to the new book that came out on his birthday: Powsels and Thrums: A Tapestry of a Creative Life. I can’t wait to get my hands on a copy when I get to England next week.

There are two other books to which I’ve been wanting to draw to your attention, both of them referenced in the new episode of The Great Humbling which Ed and I put out yesterday.

The first is Em Strang’s remarkable novel, Quinn. Anna read this over the summer and then put it on the top of the pile on my bedside table, and I’m glad she did. This is a dream-spell of a novel, conjuring the inner life of a man who struggles to hold onto the reality of a crime he has committed and who finds himself released from prison to care for the mother of his victim. It’s a meditation on forgiveness and punishment, which knows the cost of both, and which offers no neat redemptive arc.

I’ve known Em since the early days of Dark Mountain, when she worked with us as poetry editor, and she’s won awards for her own poetry. Her craft as a poet shows in this book, in her skilful handling of the uncanny, the power of echoes and repetitions, the flow and ebb of images. But the power of the book also reflects her experience over a decade working with long-term prisoners in Scottish prisons. For a novel which handles such subject matter, it’s a strange thing to call it beautiful, yet this is true.

I wanted to draw attention to Em’s book for its own sake, but also because she has just arrived on Substack, where she is writing as

:I’ve resisted opening a Substack account for years, because I’m a hermit. I like hiding. Resisting and hiding are two things I know a bit about, and I’ll be sharing snippets about these here, along with words about/towards forgiveness, God, love, and not having a clue.

There’s one more theme, not mentioned in that first post, which she admits she was afraid to mention, but which frames the invitation she makes in her second post to a conversation about “Our Violent Men”:

I’m afraid because most women and a significant number of men have been terrorised, abused or harmed by men at some point in their lives, and the damage those men caused is still – to lesser or greater degrees – held in our bodies. This damage demands a strong reaction (understandably), but I don’t want to talk (much) about that. Instead, I want to ask this: are we – as embodied beings – forever trapped inside a cycle of violence that began with the arrival of human life on the planet and continues to this day, travelling down the generations, down through years of neglect, abuse, grievance, war, cultural conditioning and repression? And this: are those of us bearing witness to the violence, and those of us who have been prey to men’s violent predation, able to end the dark cycle?

It’s a brave conversation to try to open up, one that Anna and I want to lean into, and perhaps you will join us.

The last book I want to mention is a little yellow paperback that was waiting for me when I arrived home from America. Indeed, I could say, with a nod to the Cyclops Polyphemus: “Nothing was waiting for me when I arrived home from America.”

Notes on Nothing is an anonymously published account of “a meeting with Nothing, that never actually happened.” The experience its author describes is one which may prompt recognition from those familiar with the accounts of mystics in different cultural traditions, but this is a telling which does not lean on a pre-existing framework.

Its virtues are, firstly, the skill of the writer in using words to touch the hem of an experience which takes place beyond the edge of language. And, secondly, the choice to remain anonymous, since it is almost impossible to find contemporary writing about such experiences which does not come swaddled in the marketing of Enlightenment as a consumer good.

(As I told Ed on this week’s episode, I once found myself at the back of a very packed hall in London, where the New Age celebrity Eckhart Tolle was speaking. It felt sad in the way that seeing a great ape in a concrete zoo enclosure feel sad: no doubt, this man’s life had been changed by a powerful mystical experience, but he appeared to be trapped inside the industry that had been built around his story.)

So I salute As Is Press for bringing out Notes On Nothing in a format that doesn’t lunge for the New Age dollar, but does justice to a carefully and beautifully written account of an experience at once ordinary and extraordinary.

Thanks for reading, folks. I’m putting the final words to this post from a train headed into Stockholm, at the beginning of a family journey that will take us to France and the UK over the days ahead.

This includes two public events in London, at the Kairos club on Tuesday 29th and then at the UnHerd club on Thursday 31st. The Tuesday event is sold out, but there are still a few tickets available for the Thursday.

Finally, there are still places available for both groups in the online series I’ll be teaching, Pockets, Patterns & Practices, which starts in two weeks’ time.

DH

What would be your recommended “start here” book for Garner? (Or Illich for that matter!)

Yet another soul-stirring post. Thanks!