Out there, in that Divine Dark,

Out there, in that Divine Deep,

The fishing is good,

The fishing is very good.

Out there, in that Divine Dark,

Out there, in that Divine Deep,

The fishing, not fishing at all,

Is blessedness, is bliss.

— John Moriarty, ‘Big Mike’

He stopped her by the roofless ruin of the church, pointed, heard her gasp. She stared while moonlight got past the clouds to the holed and broken walls, onto a low newer church inside the nave of the old.

— China Miéville, ‘Covehithe’

The herring catch must have been good along the Suffolk coast in the years when they built the great church of St Andrew’s at Covehithe. Back then, this little town could boast a linen trade and a late autumn fair on St Andrew’s Day. The gothic arches of his church stood tall from the turn of the fifteenth century, through the generations of Reformation and Civil War, but by the time of the Restoration, the prosperity announced by its proportions was only a memory – and so, in 1672, the parishioners were granted permission to take off the roof and dismantle the original structure. Among the ruins, making use of the salvaged materials, they built a new and humbler church. With its thatched roof and whitewashed interior, it remains in use to this day.

It was my podcasting compadre, Ed Gillespie, who drew my attention to the church-within-a-church at Covehithe. He’d heard me talk about Federico Campagna’s invitation to ‘make good ruins’, fragments that might be put to use in as-yet-unimaginable futures, and it made him think of this place where he often goes walking.

‘The church as a metaphor speaks for itself,’ he writes, ‘and chimes bells of degrowth, reinvention, resourcefulness and beauty, coupled with a brisk pragmatism.’

What Ed couldn’t have known was quite how long I had been travelling with the image of a ruined church, or how the photographs he sent would form the latest layer in a palimpsest.

Palimpsest (n): A manuscript that has been written on more than once, with the earlier writing incompletely scraped off or erased and often legible.

Maybe you know that I grew up around churches.

My dad was a few weeks into his first term at theological college when I was born. Our family lived in a two-room cottage out the back. Once I could walk, I had the run of the grounds and corridors, walled safe against cars, part of a village-scale community where everyone knew everyone else.

All through my childhood, I played around pews and pulpits. As a teenager, the choirs I sang in took me to chapels and cathedrals across the northeast of England and beyond.

I’ve made no secret of these things, but I’ve not said much about how they formed me, or what I carried with me out of these beginnings.

I’m still learning to word the parts of it that can be worded.

When I shared the earliest draft of the book that became At Work in the Ruins with Alastair McIntosh, he told me that its most important passage was the call made in the closing pages:

So, my encouragement would be to surrender, yes – but to surrender to the mystery, not the certainty. Set a place at the table for the stranger who might arrive at your door, even now, even in a world which has forgotten so much about hospitality.

Should I feel called to do so, Alastair went on, he would encourage me to take this further.

The scope of the book was already so great, this gesture towards mystery was as much as I could offer. Yet other readers have homed in on these lines, bringing me back to the door that is left ajar there, wondering what lies across its threshold.

Earlier this summer, the Green House think tank published a review essay, ‘Beyond the Fish Tank’, by the philosopher John Foster. After plenty of kind words about the book, he arrived at his main criticism:

Hine’s instinct for where renewed creative life-energy to dislodge scientism must come from feels broadly right … but he has left out what has been since before Aristotle the only reliable means of getting conceptually upstream of science’s assumptions about reality: he has left out the metaphysics.

I read this with a twitch of recognition, halfway to a smile, because it came so close to what I’d seen myself since writing the book: that its argument leaves off at the place where what is called for is a plunge into deep waters, out there where language turns strange.

And then, should a further hint be needed, the most generous review so far came from a scholar of Kierkegaard, the philosopher who gave us the image of the ‘leap of faith’.

Strange to say, in that first draft, there were hardly any ruins. The word occurs four times in twenty-six chapters, and two of those are in quotations. Anna Tsing’s phrase about ‘the possibility of life in capitalist ruins’ is there, but I had yet to stumble across Campagna’s line about ‘making good ruins’. At the time I wrote it, then, I was in no way conscious of this as a theme that might frame the book.

As an author, the cover is the one place where you don’t have a veto. Coming out of the madness of writing the final draft in ten days flat, with the book headed into production, things came to a head. None of my suggestions for a title had landed – so the publisher came with a suggestion of their own, and it soon became clear that this was what the book would be called.

At the time, this was a wrench, as though the priest baptising your firstborn got to decide the child’s name. Besides, I’d always thought of myself as good at naming things.

I can share this now because I came to see the whole business rather differently.

For a start, I remembered how many of the well-named things I’ve had a hand in creating were not actually named by me at all. When

and I started writing a manifesto, he’d already landed on the name Dark Mountain, borrowed from a poem by Robinson Jeffers. I’ve told the story of how it was Anna who saw that our school should be called HOME. Sure, I’d had some good titles for books that never got written – Changing the World (and other excuses for not getting a proper job) remains my favourite – but allowing someone else to name this book turned out to be a necessary humbling, part of letting go the baggage of those unwritten books, giving up on trying to be clever.And then this title grew on me and put down roots. Weeks or months after it had been decided, memories would surface that made me see just how long I had been working with the language of ruins.

In the end, by the time the book came out, I could barely remember feeling that its title wasn’t mine.

From the window of the West Highland Line train, rattling along the north bank of the Clyde, you get a glimpse of the extraordinary brutalist ruin of St Peter’s Seminary, outside the village of Cardross. This was the route that

and I travelled in February, bound for Glasgow, the day we launched the book.Built for the Roman Catholic church in the 1960s, within twenty years the buildings of St Peter’s were abandoned. Their concrete arches became a puzzle that no one can solve: architects declare it a ‘building of world significance’, official bodies accord it the highest level of protection for ‘special architectural or historical significance’, yet no way has been found to bring it back into use or preserve it against ongoing decay, and so the rain does its work and the forest slowly breaks in, accompanied now and then by architecture students, urban explorers or graffiti writers, adding their own layers to its palimpsest.

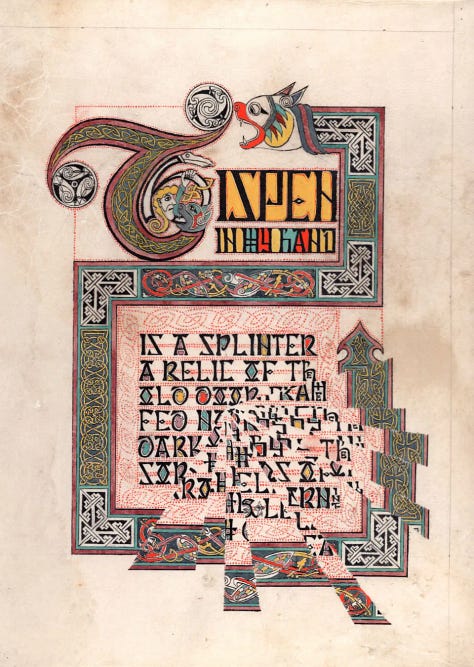

Back in 2017, I was working on the Sanctum issue of Dark Mountain, a special issue on the theme of the sacred. All the artwork for that book was to be painted on parchment, made from the skins of roadkill deer by Thomas Keyes, a graffiti writer-turned-illuminator who studies and reinvents the techniques and styles of the Insular manuscripts, the intricate creations of Celtic scribes who worked in Scotland and Ireland, twelve centuries ago or more.

We were deep in the work on that book when I was approached about the possibility of creating an event at the derelict seminary in Cardross. At the time, the site was the focus of a project to create an ‘international venue for public art and knowledge exchange’. Nothing came of that original approach, yet it planted a seed, an idea of bringing people together – literally or metaphorically – among the ruins of modernity, but also the ruins of our institutional religious traditions.

‘What encounters become possible in a time of endings?’ it says in my notes. ‘What might we meet, on this site of loss, that stayed hidden as long as these walls stood proud?’

And then, further on, there’s a suggested title for such a gathering: On Our Knees in the Ruins.

Lingering on the threshold of things I know need writing, for some weeks this spring, I republished a series of earlier essays, each of which touched on the theme of the sacred.1 At the time, I promised to end the series with the earliest piece of work I was willing to have loose on the internet. Only after I’d made the promise did I see that this, too, was part of the palimpsest I am tracing here.

It’s a poem I started writing on a roadside in Belgium in November 1996. I was about to turn nineteen, hitchhiking with a guitar and an overweight rucksack, at a time of year when the weather and the light are often against you. The remaining lines arrived a few weeks later, walking alone on a winter’s afternoon along the banks of the Meuse at Namur. The title came from a man named Johnny Norris who gave me a lift the following June, headed north along the Finnish-Swedish border.

I don’t make much claim to be a poet, but in the years that followed, I would write hundreds of thousands of words of all kinds before I came out with anything else that I’d be willing to share with you today.

So here it is, my first brush with the image of the ruined church.

The Church of the Blue Dome

Horses from my window, under a lifting sky. November sunshine comes, unlooked for, takes me, lifts me, bears me high and I am reconciled to life once more. I never found joy. It sought me when all my faith was gone, and caught and killed my disbelief in perfect colour of turning leaf or winter setting sun. So let the churches lie in ruins — all things crumble, by and by — until some stranger seeking a place of refuge from the human race stumbles on the wordless grace of altars under autumn skies.

One Sunday in February this year, I woke in the Welsh borders and zigzagged cross-country by trains and rail replacement buses as far as Peterborough, where my dad picked me up in the station carpark. He’d come straight from a meeting where he and his fellow members had taken the decision to close the local church where he has worshipped and led services since his retirement.

When a church closes down these days, they don’t take the roof off. The building goes on the market and, depending on the location, becomes a carpet shop or a bar or a set of flats. Meanwhile, old men sort through hymn books and banners, strain themselves to move pianos, deal with utility companies and insurance.

Within the story of modernity, these closures are just the tying up of so many loose ends: nothing to see here, nothing to be curious about, only the playing out of a process of secularisation, as we shed the last habits of an earlier and more ignorant way of inhabiting the world.

If you have come to suspect that too much was left out of the story of modernity, that its vessel is cracked and no longer holds water – and these allegations run through everything I write – then the closing churches invite a closer attention.

At Covehithe, they made a humbler vessel from the salvage of a grandeur that could no longer hold: a life-raft that has lasted three-and-a-half centuries. There are lessons for us here, no doubt, as Ed suggests. Yet even this life-raft won’t last much longer. The sea is coming, the shoreline moving fast inland. The cliffs are a field away and closing in. Somewhere within the next two or three generations, the village and its church-within-a-church will be gone.

I heard a story somewhere as a kid about a church whose roof was made from a ship: her sailing done, her masts lopped off, she ends her days upturned, sheltering worshippers from the elements.

Not sure how this carpentry would work, I search the internet, hoping to locate the truth behind the story. No joy, except that I am reminded that every church is already a ship: the nave, the main part of the building, named for the Latin navis and the mirroring of a wooden vessel in the roofwork.

A thought comes, or an image: maybe that’s what happens next, what you’re left with, when it’s time to take the roof off and leave the altar to receive the quiet blessing of an autumn sun. You turn the vessel upside down, you remember that it was a boat all along, that it wasn’t meant for the safety of dry land, but for heading out over dark waters, into the deep, where the fishing is not fishing at all.

Thanks for bearing with me, folks, through the quiet weeks of summer and the journey that led to this piece. Looking back, I’ve been headed into these waters since I started this Substack with ‘Setting Out Once More’, and ‘There Are Signs’ was a flare sent up before the summer.

Clearly, there’s more where this one came from. From what I can make out, it’s the first in a sequence of four pieces whose shape came into view during the time spent away from screens in July. It’s also part of the larger pattern I had in mind, returning from Patmos: ‘I find myself writing things that loop around the whorl of this experience like the lines on a thumb print’. If you’re wondering where all of this is headed, then, bear with me a little longer and the pattern may become clearer. Or not!

The support of paying subscribers is what makes it possible for me to devote time to writing the letters and essays that I publish here. If you appreciated this piece, then please consider joining them:

Finally, a particular thanks to

for putting into my hands a copy of The Hut at the Edge of the Village, the collection he edited of John Moriarty’s writing, which is where I met the story of Big Mike.DH

The series started with ‘Childish Things’, written for the Sanctum issue of Dark Mountain, then ‘The Crossing of Two Lines’ and ‘A Place Where Magic Could Happen’.

I sat with a stranger for lunch once. She wore beads and braids and the dark skin of her old African homeland. She, like I, was a preacher's kid who no longer practiced Christianity. She described her year-long initiation to her Yoruba Orisha. Our conversation, in just half an hour went deep in a way that made the rest of the world--in this case a bustling food justice conference--recede into the background. Before we parted ways, she told me that her father, a retired preacher like mine, prays every morning for his next divine appointment. She said, "Adam, we just had one of those."

There's so much in what you've shared here, Dougald. The church within a church. The state of un-belonging. Thank you for laboring to gather these potent words.

This really comforts me and I can’t fully explain why. The metaphor but also the idea that we physically build within the crumbling walls new ways of worshipping the Earth and slip backwards to reclaim what was there before those big churches came. There is a truth here, a simplicity, a homecoming and I find the thought of it so beautiful. I’m looking forward to the next part.