This is the third part of a series that began with ‘The Ruined Church’ and ‘Stranger Friends’. With any luck, the next of these essays should bring the series to a close, to be followed by an exchange of letters with the artist and theologian Vanessa Chamberlin. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to interleave this kind of writing with posts which follow up on other themes from At Work in the Ruins, as well as a new series of The Great Humbling podcast, starting in early November.

Finally – and connected to this week’s post – I’m taking part in a fortnightly series of Illich Conversations which starts this Sunday at 8pm UK time. These Zoom events are hosted by

and in the opening session, I’ll be in conversation with the Canadian broadcaster David Cayley, a close friend and collaborator of Ivan Illich. Paid subscribers to this Substack are welcome to join us live, so if you haven’t done already, then this would be a good moment to sign up:I’ll send out full details of how to join Sunday’s call in a post for paid subscribers tomorrow.

Now, on with this week’s essay…

“Insist too hard on the significance of a poetic coincidence and you will make people uncomfortable. Better to recount such moments as jokes the world seemed to join in with than as some kind of revelation.”

(from an essay I wrote in 2014)

“Then someone laughed. Thank goodness. A chuckle that gave permission for the whole room to break: break into uncontained giggling, into a humble beginning, into some semblance of understanding. I often reflect on how much the apocalypse needs comedians.”

(from

’s newsletter this Sunday)I was on my way to Patmos – which, as you may know, is the island of the Apocalypse, the place where a man named John wrote what ended up being the last book of the Bible. And before all the other things it came to mean, the word apokalypsis meant ‘uncovering’, ‘unveiling’, the moment when something hidden is brought into view.

People asked if this was some kind of pilgrimage. Well, not to my knowledge. I was going to the first international gathering of Black Elephant, a movement started by a group of recovering addicts to share what they had found in the rooms of Twelve Step fellowships with those of us whose lives never took the kind of turn that leads to those rooms. I’ve told this part of the story before.

But I’d be kidding if I said the significance of the destination wasn’t on my mind. I’d just written a book that opened with a line about ‘living at the end of the world as we know it’. In the conversations this led me into, there seemed to be a gravitational pull towards some kind of reckoning with the religious tradition into which I was born. And when, a week before the trip, John Foster’s review of my book declared that there was one thing missing – ‘he has left out the metaphysics’ – well, that caught my eye, because the Black Elephant gathering was actually called Meta+Physics.

So yes, alright, I was on my way to Patmos with a sense that something might be revealed. This journey had hovered on the horizon for months; it seemed to be part of a pattern within which I was being carried, and the part of me that takes such patterns seriously was half-expecting something to happen. I just didn’t expect it to happen before I got there, before I had even reached the airport, thirty miles from home, as a man held a blade to my throat.

To tell you this story, I need to roll things back to three days earlier.

There’s a gathering I go to on Tuesday afternoons. Often, though not always, it is my role to host this gathering.

It happens in the in-between space which you no doubt know: the Zoom-space where our different rooms and timezones and seasons tesselate and where, with luck, imagination may just bridge the gap of all that doesn’t carry through cameras and screens.

The rhythm of regular gathering helps with the bridging. As the Australian artist Kelly Lee Hickey put it to our group, ‘Time becomes the space in which we meet.’ Returning to the same pocket of time, over weeks and months, there is a gentle deepening. Something is waiting to receive us, like the nest of flattened grass that a hare makes, a form created by the returning presence of a body.

There can be anywhere between six and twelve of us on a Tuesday: a few regulars who rarely miss a week, others who pass through when they can and when they need it. We meet for an hour. The invitation is simple: share what is on your heart. It may be something you brought with you or something that bubbles up as you listen. Surprisingly often, it seems – as someone said after an early meeting – we all go away with a gift that nobody brought.

On that particular Tuesday, the group included my friends Helen and Liz.

Helen spent thirty years working deep inside the European Commission. These days she makes singing bowls and welcomes visitors at the kachel, the clay oven that is the hearth of the home she has made with two other women on a patch of land in a Flemish village.

Liz and I met when she wrote an essay for Dark Mountain about her journey as a scientific atheist who fell into a deepening relationship with the sacred. These days she’s the leader of a national church and her WhatsApp messages are as likely to be about the future of disused chapels in English seaside towns as the latest famous artist she’s found herself deep in conversation with about ‘the God-shaped hole’ in our culture.

At the end of our gathering that day, I spoke about the trip to Patmos, the combination of people I was going with, the sense of something coming to a head.

‘Well, just don’t come back a Christian!’ Helen said. ‘We’ve got enough of those already!’

Elsewhere on the screen, I saw Liz frown and heard her say, ‘I think it might be… a bit late?’

I smiled and didn’t add much – anyway, it was time to sound the singing bowl to end the session – but I went away pondering these things. It wasn’t just that two friends with whom I had shared a good deal should have contrasting assumptions as to whether or not I was ‘a Christian’. It was that this question had never arisen in all the years of my public existence, since I began to write and speak in places which meant that people whose names I didn’t know knew mine. Never arisen, that is, until now.

The next morning, the episode of The Sacred dropped that I’d recorded weeks earlier with

, who was also coming to Patmos. There’s no smalltalk on Elizabeth’s podcast. She plunges her guests straight in with the opening question: ‘What is sacred to you?’For me, the language of ‘the sacred’ points to that which is radically other. Religion and spirituality are human constructs – shelters we build to invite or hold onto encounters with the other – but the sacred names what lies beyond these shelters, the experience which compels us to construct them. The sacred may be encountered, but such encounters bring us to a place where language fails. In all the traditions I’ve spent time around, there seems to be an acknowledgement of this in the deliberate strangeness of the use of language. Think of the unpronounceable name of G-d in the Hebrew Bible, or the first lines of the Tao:

The way that can be spoken of is not the eternal way;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

So we spoke about these things and Elizabeth led me to retrace the path of my own formation, growing up around churches. What I notice listening back is a carefulness in my choice of words, a studied neutrality, and the polite distance that this establishes between us. ‘In my language,’ she will say, and ‘in my tradition’, meaning the Christianity that is central to her public identity.

Midway through our conversation, I found myself telling a story that I had told only once before. It’s about an experience I had one Easter Sunday, around the time I turned thirty, at evensong in a cathedral in a city in the north of England.

Each episode of The Sacred ends with a reflection which Elizabeth records near the end of the editing process. Looking back over our conversation, she picked up the thread of this story I had told. For her, it seemed emblematic of the experience of many in our generation, those who grew up with Christian parents, but for whom – as she put it – ‘that inheritance failed to pass.’ In what I had described, she heard an experience of ‘feeling the need to let it go’.

There’s truth in those words – and still, as I heard her tell it back, I had a sense that there was part of this story I did not yet know how to tell.

There are kinds of Christian worship which are constructed so as to bring on an intensity of experience – standing, swaying, arms raised, eyes closed and face upturned – but this is not what you will find in an Anglican cathedral at evensong. A seated congregation scattered through the pews, following the words of the liturgy in a book.

I was raised in a Reformed tradition which was full of hymns and prayer and preaching and put less store by formal liturgy. But already in my teens, through schools and choirs, I came in contact with the Prayer Book and found shelter in the familiarity of its forms. Through my twenties, I drifted from church to church, but I was usually a semi-regular attender somewhere, joining the small evening congregation in a local parish or going to a Quaker meeting. My life in those years lacked stability or a clear sense of direction and, for this reason, if no other, I never really became an active member of a congregation. From the perspective of the church as community, I was hovering in the doorway.

Yet if I had not found a way of fully belonging to a church, it was more than just a lingering sense of obligation that kept me going. The patterns of repeated words were a room to which I kept returning, its stone floor worn smooth by all the feet that had passed this way before. For one hour in the week, I knelt on ground where generations had knelt, speaking words which they would have recognised. And now and then, I would encounter something else in that room, a relationship with what lay beyond the limits of language and behind the surface of everything.

By the year I turned thirty, my drifting had brought me to the cathedral – and so, on this Easter evening, I was listening to the Gospel reading when there came a sudden, quiet but forceful sensation, an experience which had two sides to it. On the one side, I had the sense of listening to a joke which had been retold so many times that everyone seemed to have forgotten this part was meant to be the punchline. On the other side, there was a release from any need to try to belong to a church or to speak in the language of this tradition out of which I came.

These were not statements that I could reasonably express or defend, to try would have been to miss the point. Fifteen years would go by before I felt any need to tell this story. But now that I am doing so, some explanation is required, or what it meant to me will be misunderstood.

The first thing to know is that, in the year or two before that evening, I had spent a lot of time in comedy clubs. I never tried standing on stage, but I learned a lot from those who did – some good, some bad, some famous – while I helped out on the door, stood at the back or sat in the front row. I began to notice how the whole thing hung on taking a collection of individuals, drawing them into a shared consciousness, then seeing where you could ride that consciousness and what shapes you could draw it into. I came to think of stand-up as the one shamanic form indigenous to modern urban culture. I’d started thinking, too, about the moment when you get a joke: how you have no information you didn’t have a moment earlier, yet your experience is transformed.

All of this to say that, for me, just then, to call something a joke was by no means the dismissal it might have been in someone else’s mouth. There was no bitterness here, no alienation, and yet what happened in the cathedral marked a turning point. In the months that followed, for the first time in my life, I fell out of the habit of churchgoing altogether, and that has remained the case.

This coincided with the beginning of what I called earlier my ‘public existence’. Had you known me in my twenties, it would not have been long before you heard me talk about Garner, Illich and Berger. These were my names to conjure with, the three old men whose books were the constellations I learned to steer by. Then, in the space of a few weeks around my thirtieth birthday, I saw John Berger speak, asked Alan Garner a question which led to an invitation to visit his home, and found myself travelling to Mexico to meet the surviving friends of Ivan Illich. I had been looking at a painting on a wall, now I stepped through the frame and into the scene.

A year would go by before I found a voice of my own and discovered that people would listen, but this sequence of encounters was where it started. There was, in other words, little overlap between the time in my life when I was a churchgoing person, when the words I used to talk about myself and the world drew from the tradition into which I had been born, and the time in my life when I had a public voice.

I was well into my forties before I discovered the pleasure of having a man lay hot towels across my face, anoint my skin with mysterious oils and take a blade to my throat. From childhood, I’d squirmed at the chattiness of hairdressers. There’s decades of photographic evidence of the lengths to which I would go to avoid such encounters. But the proximity of sharpened steel puts a limit on chat and I’ve come to count it as a luxury to submit to the handling of a barber who knows his tools. I still go around growing fuzzy for months at home, but a few times a year, when I’m headed out into the world, I’ll make this a part of the ritual of departure.

So it was that, on the first Friday in June, when I left home to begin the journey to Patmos, my first stop was a barbershop in Uppsala. It was mid-morning and I was the only customer. I lay back in the leather chair. There was a playlist going in the background, but I don’t remember anything about it, until the song came on.

It was a cover version, not a particularly good one, and when I tried looking it up later it turns out there are plenty of them, but my first thought was that I’d never heard a cover of Losing My Religion.

My second thought was that I had sung this song myself more times than any other. As a teenager, in the year I spent busking my way around Europe, it was my theme song: the sweet spot between what sang to my heart and what would make passersby smile and stop to listen or reach in their pockets. REM were massive in the mid-nineties. You could play that song in any country in Europe and groups of school kids, students or football fans would sing along. I played it everywhere from the Arctic Circle to Istanbul, and unlike some of the other songs, it never wore thin on me. Though I never again lived by music, my guitar would still come out at gatherings, and so I can remember singing it late at night on the steps of New College mound in Oxford, straining my voice to sound like Michael Stipe, and on the balcony of the Green Elephant hostel in Cape Town and at a gathering of the friends of Ivan Illich in a villa in the Tuscan hills.

My third thought was the one where it went click. Oh, I thought to myself, that’s what happened. The thing I hadn’t named clearly about that night in the cathedral, the part that I’d left out, the reason I didn’t quite recognise my story in Elizabeth’s telling it back to me, when I heard her say that the inheritance didn’t pass.

I never lost my faith, you see – what I had lost was my religion.

Now, you can make of this what you will. I am not trying to stake a claim.

In many ways, I have been happy in my reticence, not needing many words for this inheritance, letting people take me as they find me.

In the years that followed that night in the cathedral, I travelled a long way from home and dwelt on the wild edges of other people’s traditions. I’m grateful for the hospitality I found there.

I worked with and learned enormously from people whose own inheritance includes great damage done in the name of Christianity, and that alone was reason to say little.

And I’m not especially interested in being right – at least, I’ve learned not to trust the part of me that sets store by this – or in having a badge of identity to wear and a banner to march under.

For a good while, in the worlds in which I moved, it hardly seemed possible to speak from any kind of grounding within Christianity and have a chance of being heard. That has shifted in the past five years, and the pull to tell this part of my story comes because there are wider conversations to which I want to contribute, and I can’t do that while pretending to speak from nowhere, or hiding the wells from which I draw.

Yet I remain uncomfortable trying to put something this intimate into words.

At this moment in the writing, a message arrives from a dear friend, speaking of how something broke open for her this autumn, when someone said to her, ‘I’m not not a Christian.’ Something has come back, she says.

Over the summer, I reread The Rivers North of the Future, the book that David Cayley made out of his late interviews with Illich. In those interviews, Cayley’s aim was to draw out the argument of a book he had realised Illich would never write – a book about the deep roots of modernity in the institutionalising of Christianity. So the two friends collaborate to trace an historical argument, but inevitably the conversation veers at times into the territory of faith, and I take heart from the discomfort Illich expresses in moments like this:

It’s a very intimate thing I say to you, and I’m really embarrassed to say it in front of these microphones you have put on my desk here in Ocotopec. Nevertheless, I dare it. I don’t risk it; I dare it. I dare to allow people to listen to how I speak to a friend.

There are things that can only be spoken in the way that I speak to a friend, written as though I am writing a letter to one whom I know and trust, who remains mysterious to me, as we all remain mysterious to one another.

So let’s draw a line there for today: whatever else, I can say with my friend’s friend, ‘I am not not a Christian.’ I too have the feeling that something has come back. And, after all these words, I suspect that friends will still arrive at contrasting conclusions as to what I may or may not be. Which is fine.

It is not quite the end of the story, though.

I went to Patmos and plenty of things happened, though none that eclipsed that moment of clarity in the barber’s chair.

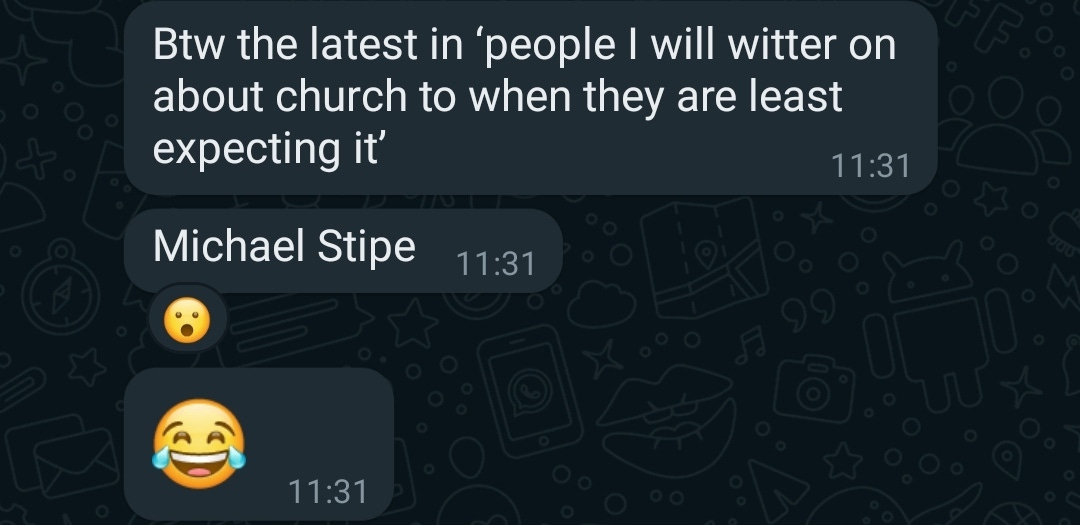

And then, four days after I got home, before I’d had the chance to tell her any of what I’ve told you here, Liz dropped this into the group chat:

And I mean, seriously, to talk about punchlines, how’s that for a joke the world joined in with?

Thanks for coming with me on this journey. I’m still shaking my head at the Michael Stipe bit.

As I say, you can join me and David Cayley for a live conversation on Zoom this Sunday, 15 October 2023, at 8pm UK time. (That’s 3pm on the East Coast, noon on the West Coast, or 9pm for those of us in Sweden.) To get onboard for that, sign up as a paid subscriber to this Substack and look out for the full invitation which I’ll be sending tomorrow:

The fourth and final instalment in this series is coming in a few weeks’ time. I can tell you that it starts with Vishnu sitting on the top of Chongolungma.

Meanwhile, I have other things to write about and other invitations to share in the weeks ahead. Thanks to all of you who have been commenting on and sharing these posts. It’s great to have your company and support.

DH

Thank you for reaching deep inside the bag of your inner life, Dougald, to pull out this offering to share with us! I suspect that your impeccability as a wordsmith will always prevent you from making sweeping statements about faith or reality! I am always amazed at the things you remember (harking back to yesterday's Long-Table weekly heartbeat call, where you confessed that Anna had said you remembered everything but the important things (like putting the dustbins out...)) - that totally unpremeditated but heartfelt blurt of mine about "as long as you don't come back a Christian"... There is something in me that would welcome a mutual groping-around-in-the-bag conversation about all of this. It's so deep and so ungraspable and yet so tangible at the same time. You're opening up a very fruitful and subtle and complex terrain here for us to treasure hunt in.

I am watching this unfolding -- you, Martin Shaw, Paul Kingsnorth, maybe Caroline Ross--with fascination. And two things occur to me:

1.) that I have a sense of how similar to early Quaker history it all sounds; trying to pry some kinds of core truths away from the greedy grasping hands of the Establishment Church, seeking the "beloved community," being called to "speak Truth to Power."

2.) I'm told that it is not uncommon, within certain castes in Hindu India, for men of a certain age to walk away from their families and their material lives in search of some sort of deepened connection with God...

And along with your "impeccability as a wordsmith," I'm always struck by your deep and abiding kindness. That instinct is surely part of what is sacred to many of us as we explore the ruins of modernity. And a way in which you and Vanessa surely meet on common ground. Thank you for doing this work.